Sections / Articles

Turn Up the Volume

Authentically give students a voice in your school—and listen.

By Russell J. Quaglia and Michael J. Corso

Principal, January/February 2016

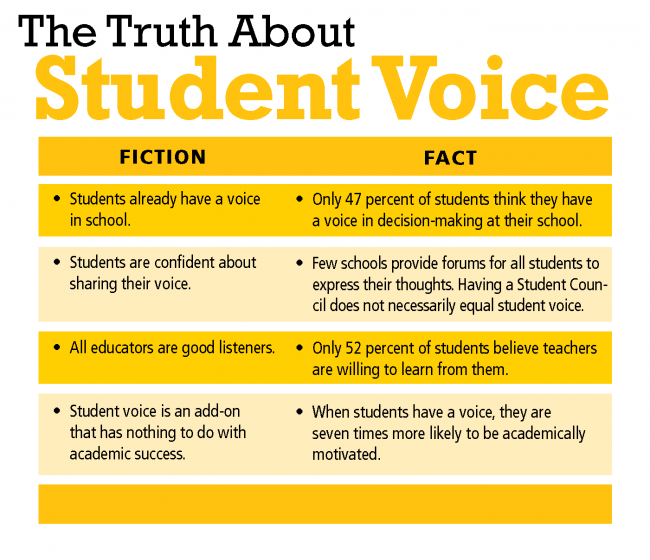

Student voice is a simple concept that happens by the very nature of students wanting to tell us what they think. Even when they do not readily offer it, we ask students their opinions all the time. And whether offered or asked, given their unique perspective, we are open to their suggestions about how to improve our schools. Right? Wrong.

Student voice can refer to something as simple as students deciding what to display on the bulletin board, or as challenging as them serving on a search committee for a teacher. Regardless of the complexity of the situation, students have an opinion and it needs to be heard.

Unfortunately, meaningful expression of student voice in schools is not a natural occurrence. But it needs to be if we expect students to reach their fullest potential. Principals have the power to change all that, amplifying student voice and ultimately students’ education experience.

Before you say, “Not another sappy article about how we need to listen to students because they are our greatest resource,” let’s start with a bit of data: Students who believe they have a voice in school are seven times more likely to be academically motivated than students who feel they have no voice. That is the resounding say-so of tens of thousands of students from all over the country in all kinds of schools. If you know something else that will have a seven-fold impact on your students’ motivation, stop reading this article and go do that.

There is no age requirement for students to have a voice. While we believe this effect is in place as early as grade 3 and younger, sadly the percentage of students who believe they have a voice in school steadily declines from grade to grade.

Call to Action

Students with a voice have the ability to speak openly in an environment that is driven by trust, partnership, and responsibility. Student voice is about listening, learning from what is being said, and taking action together.

Here are a few critical factors needed for student voice to flourish:

- Students need to learn how to express their voice in a meaningful way;

- Principals need to be willing to listen and learn from what students are saying; and

- Principals and students must work together to take action on what has been learned.

Students should not only be expected to share their voice and be heard, but they also should be expected to take responsibility for putting their voice into action to help others. Student voice consists of far more than an opinion survey given once a year so that we can check the box “surveyed students.” Empowering students to take their voice and turn it into a call to action is what genuine student voice is all about.

The good news is that principals hold the key to taking a concept like student voice and turning it into an actionable item where positive changes for students can be realized. Here are some examples:

- An elementary school principal gave his students a greater sense of importance in their classrooms by listening to student ideas about how teachers should call on them. Students preferred the use of random systems (e.g., pulling Popsicle sticks with names) over traditional raise-your-hand methods.

- A middle school principal solved his school’s tardiness problem by listening to students’ suggestion that they stop marking class time throughout the day with the school bell. This action shifted the burden of responsibility for being on time from what students considered to be an outmoded system for synchronizing time (their mobile devices do that) onto the students themselves.

- In a K-8 school, students helped the principal solve the perennial battle over the dress code and the resulting loss of instructional time. Students developed a new, reasonable dress code that they are responsible for enforcing. As a bonus, this action also solved a staff morale problem that stemmed from inconsistent enforcement of the previous dress code.

Examples of principals taking students’ ideas and suggestions seriously are on the rise. These principals, and others, have realized the truth that students are not our customers or clients— they are our partners. As a result, these principals take steps to turn up the volume on student voice. You can do the same.

Take Three Steps

1. Take a listening posture toward all students. Such a stance of receptivity and openness is best done in an environment that is comfortable for students. Try these strategies:

- Leave cafeteria supervision to others and devote significant time to eating with students. Bring cookies.

- Spend less effort monitoring the hallways and do more “walk and talks.” Ask students how they are doing—and wait for a response.

- Invest less time in worrying about where your students are coming from and more time inquiring where they are going. Ask about their next class, the upcoming weekend, plans after high school, and who and what they hope to be.

2. Take what you have heard and learn from it. Recognize that your students, no matter their age, are the foremost experts on being a student in your building. They know things you don’t. So seek their innovative solutions to problems adults have spent decades not solving.

Resist dismissing student opinions you don’t understand or disagree with as “just what the kids think.” Your excuse or rationale will always be a poor substitute for their own explanation. Make every effort to understand why they are saying what they do.

For example, test scores represent one measure of important academic outcomes, but they have become an unhealthy obsession. Put them in perspective by learning your students’ hopes and dreams and measuring your school’s progress toward helping students achieve their aspirations.

3. Take what you have learned from students and lead with them. Invite students to bring solutions, not just problems. Then provide the support and resources they need to implement their solutions. Allow students to sit at the table where meaningful decisions are made. Unless another student’s confidentiality is at stake, students should be involved in every decision we make that will affect them. They don’t make the decisions—that’s what we’re paid to do—but they should be at the table as our partners.

Meaningful Engagement

Spend less time being director and actor in the long-running performance that is your school. Find every opportunity to give students center stage and keep rotating different students into that role, as well as into supporting roles. Prepare them to lead orientation, make announcements, participate in peer mediation and adjudication, welcome transfer students, seek community support, and meaningfully present (not be a dog and pony show) at board meetings.

Once you open your ears to student voice, and open your mind to their ideas and your hand in a gesture of partnership, there is no limit to the positive impact. Their honesty will be a refreshing change from the political game-playing that dysfunctions in far too many schools and districts. Their youth and naiveté will bring novel, unjaded perspectives to the “same-old, same-old” we keep trying to make solutions out of. Their enthusiasm to participate with you to improve their learning environment will fuel your own passion to make a positive difference for all students.

After all the emails have been sent, all the data poured over, all the central office meetings attended, and all the paperwork filled out, you may wonder why you became a principal. Why you remain a principal is to make a difference for kids. The bottom-line questions will not be about test scores or budgets or adequate yearly progress, but about whether you have listened to, learned from, and led with your students.

Russell J. Quaglia is president and founder of the Quaglia Institute for Student Aspirations.

Michael J. Corso is chief academic officer of the Quaglia Institute for Student Aspirations.

Copyright © National Association of Elementary School Principals. No part of the articles in NAESP magazines, newsletters, or website may be reproduced in any medium without the permission of the National Association of Elementary School Principals. For more information, view NAESP's reprint policy.

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| QuagliaCorso_JF16.pdf | 202.68 KB |

| StudentVoiceTable.pdf | 31.47 KB |