Sections / Articles

Reading Across & Within the Curriculum

Best practices to support cross-curricular literacy instruction.

By ReLeah Cossett Lent

Principal, November/December 2017. Vol. 97, Number 2.

Reading has changed significantly in the past few decades, especially after the National Reading Panel targeted five components of reading (phonics, phonemic awareness, comprehension, vocabulary, and fluency) and started a flurry of reading strategies across all grades in virtually all schools. The introduction of the Common Core State Standards in 2012–2015 further accelerated changes in reading instruction.

Teachers, even those in math and science, were required to become “teachers of reading” by learning reading strategies and then instructing students on how to use them before, during, and after reading. Today, most students beyond second grade now know how to “visualize” or “chunk” text and enjoy listening to their teachers “think aloud.” Students did, indeed, learn the strategies, but two problems arose.

First, students knew the names of the strategies and what they were to do with them, but they didn’t necessarily know how or when to use them. They relied on their teachers to give them just the right graphic organizer to go with a certain text, for example, or to tell them when it was time to make a prediction. Students did not become flexible, self-regulated readers because they had not internalized the strategies and learned to use them as proficient readers do.

The second problem was that generic strategies failed to acknowledge the vast differences among the disciplines and the unique ways scientists, historians, writers, poets, and mathematicians approach text. The strategies didn’t help students understand how texts in various disciplines differ. A prediction in science (called a hypothesis in scientific vocabulary) is not like a prediction in a short story; each requires different understandings and skills. What became evident, as is often the case with silver-bullet remedies to complex problems, is that generic reading strategies alone are not sufficient to help students read the complex texts associated with content-area learning in later grades. Most educators agree: It’s time for a shift. But what exactly are we to shift toward? And how are principals to support and encourage still another change without making their teachers crazy? This time, the answer may be easier than we thought.

A Shift Toward Disciplinary Literacy

Learning to read fairly similar texts in the early grades doesn’t fully prepare students to decipher the wide variety of text structures, vocabulary, purposes, and visuals unique to specific disciplines. Students in social studies classes, for example, need to be taught how to “read” primary documents such as photographs, certificates, letters, manifests, diaries, opinion pieces, or maps. That’s in addition to more traditional texts that describe, analyze, explain, or persuade. Teachers must help students understand how historians approach each of these texts, which skills they need to develop to make sense of the text (such as understanding bias), and how one aspect of the text might be particularly important in history but not so important if the document supplements a story in an English language-arts class. Similarly, a science teacher must help students develop the skills required to read—and write—lab notes; math teachers should teach skills that help students tackle a word problem.

Imagine the flexibility and skill with which a student might read if she is taught how to approach various texts in discipline-specific ways instead of reading in only one way. This approach, called disciplinary literacy, makes sense and can lead to schoolwide comprehensive reading instruction that allows teachers to use reading, writing, and thinking as tools to help students learn content more deeply.

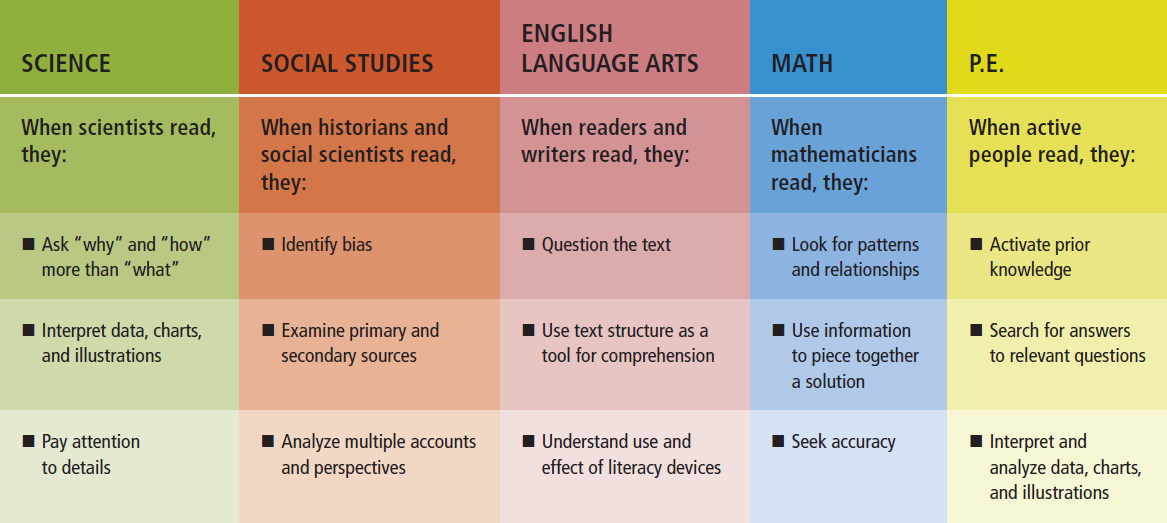

How is a principal to support such instruction? A school district in Union County, North Carolina, brought teachers together and asked them to brainstorm a list of skills students needed in order to read in their content areas. Then, teachers looked at some of the content-area skills I provided in my latest book, This Is Disciplinary Literacy: Reading, Writing, Thinking, and Doing … Content Area by Content Area as a means of comparison. They created a chart that looks something like the one below and asked teachers to contrast and compare skills students might need to become proficient readers across the disciplines.

(Click to enlarge)

It’s not enough to simply identify skills, however. Teachers must know how to teach the skills they have identified, not as an add-on, but as an integral part of their curriculum, preferably through communities of learning (grade levels, teams, content area teachers, or cross-curricular cohorts). In order to develop these skills, teachers need a time to meet, supported risk-taking and decision-making, and tools for new learning, perhaps in the form of a book study, coach, or consultant.

A Shift Toward a Schoolwide Culture of Literacy

Another way principals can support a cross-curricular approach to reading is to enthusiastically promote a schoolwide culture of literacy. When I was recently asked to assess a school in terms of its literacy challenges and strengths, I noticed a decided lack of texts other than textbooks. In meeting with the principal of this low-socioeconomic school, I discovered that a lot of money had been spent on reading programs and test prep, but the library was lackluster (and rather lonely)— and, worse, there were few engaging books for students to read independently. Many of the school’s literacy issues were eventually solved through a concerted effort to place a wide variety of books in classroom libraries, renew the focus on reading for enjoyment, and engage teachers in professional learning about how to increase reading in every single content area. In short, creating a culture of reading schoolwide made all the difference.

The following tips can help principals support and sustain a schoolwide culture of literacy:

- With a literacy leadership team, create a literacy plan for the school that sets expectations for wide and diverse reading for every student in every class, every day.

- Encourage the use of text sets in place of using a textbook as a sole curriculum resource. Summer is a great time for teachers to create rich text sets on commonly taught units. Librarians can also support their efforts.

- Find funds or have the leadership team write grants for classroom libraries in every content area, even art and P.E. Be sure and get input from teachers (and students) before purchasing books.

- Create summer reading programs that encourage reading for fun and provide ways for all students to gain access to books. One school in Illinois wrote a grant that provided each student with her choice of a top 10 book that she could take home and read during the summer. The first day back at school, teachers staged a reading celebration in which students exchanged books and engaged in discussions about their reading.

- Have a “whole-school read” of a single nonfiction article, blog, or commentary from various content areas once a week to encourage discussion around text. Sources such as DOGOnews, Smithsonian’s Tween Tribune, and National Geographic Kids are full of engaging articles in all content areas. Teachers of children in primary grades can do read-alouds or even talk about the articles so young children also can be a part of the school community.

- Resist offering incentives for reading. We want children to find joy in the act of reading, not simply to read for a grade or other extrinsic prizes. As such, encourage teachers not to test or grade independent reading. Children in all grades are eager to read and can become absolutely addicted if they are encouraged by teachers and peers.

- Encourage teachers to read books themselves so they can find the best books for their students. In a school in Georgia, all teachers were asked to choose one book to read from the International Literacy Association’s Choice Reading Awards and share it with colleagues during a faculty meeting as a way of promoting a culture of schoolwide literacy.

- Encouraging reading across and within the curriculum means looking inward to the teachers who best know their content, providing the necessary literacy learning in a collaborative setting, and supporting all of this work with a strong schoolwide culture of literacy.

ReLeah Cossett Lent is an international consultant and author of numerous articles and books, including This Is Disciplinary Literacy: Reading, Writing, Thinking and Doing … Content Area by Content Area.

Copyright © National Association of Elementary School Principals. No part of the articles in NAESP magazines, newsletters, or website may be reproduced in any medium without the permission of the National Association of Elementary School Principals. For more information, view NAESP's reprint policy.

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| Lent_ND17.pdf | 7.12 MB |