Sections / Articles

Literacy Language Learning as Partners in the Classroom

Supporting English learners in the classroom requires seeing students as both literacy and language learners, even in the earliest grades.

By Adria Klein, Janeen Zuniga, Allison Briceño, & Anette Torres Elías

Principal, September/October 2017. Volume 97, Number 1.

“We are all English learners” is a phrase often used in articles and presentations. In practice, however, the challenges of having students who speak different languages may seem overwhelming. Serving the wide range of English learners (ELs) is an important matter for principals, particularly in the many schools experiencing changing demographics and struggling to serve a more diverse population. The ways in which students are supported in the classroom—small group push-in and pullout plans, and one-on-one intervention services—all must be considered at the school and district level. Principals can influence ELs’ progress by empowering teachers to provide genuine learning opportunities, enabling teachers to collaborate and share expertise, and supporting the concept of teaching for transfer.

“We are all English learners” is a phrase often used in articles and presentations. In practice, however, the challenges of having students who speak different languages may seem overwhelming. Serving the wide range of English learners (ELs) is an important matter for principals, particularly in the many schools experiencing changing demographics and struggling to serve a more diverse population. The ways in which students are supported in the classroom—small group push-in and pullout plans, and one-on-one intervention services—all must be considered at the school and district level. Principals can influence ELs’ progress by empowering teachers to provide genuine learning opportunities, enabling teachers to collaborate and share expertise, and supporting the concept of teaching for transfer.

Designing a Professional Development Plan

Since ELs are learning to read in a language in which they aren’t yet fully proficient, their teachers need to know a lot about language development and literacy instruction. Principals can help their staff develop expertise in these areas by providing opportunities for teachers to participate in professional development (PD) that focuses on advancing teachers’ knowledge, rather than showing them how to use a program. Forming collaborative learning teams can then enable teachers to share knowledge among themselves. PD should support teachers in their ongoing learning and enable them to become self-directed learners.

When principal Janeen Zuniga arrived at her neighborhood elementary school in California four years ago, the school was known in the community for serving its diverse population of students well—teachers with high expectations, low discipline rates, and strong standardized test scores. Zuniga noted, however, that in a school population of 23 percent ELs and 67 percent socioeconomically disadvantaged (SD) students, only 3 percent of the EL students were gaining enough English proficiency to be redesignated as fluent English-proficient. And approximately 12 percent of the general education students were identified for IEPs by grade 4. In addition, retention of students was considered for those not showing proficiency on state tests and district common assessments.

Zuniga worked with the dedicated teachers and School Site Council members to design and implement a school literacy plan with a four-tiered RTI model of instruction and intervention. Based on Linda Dorn’s Partnerships in Comprehensive Literacy Model, the plan drew an implementation design from the 2011 Dorn and Soffos Interventions That Work: A Comprehensive Model for Preventing Reading Failure.

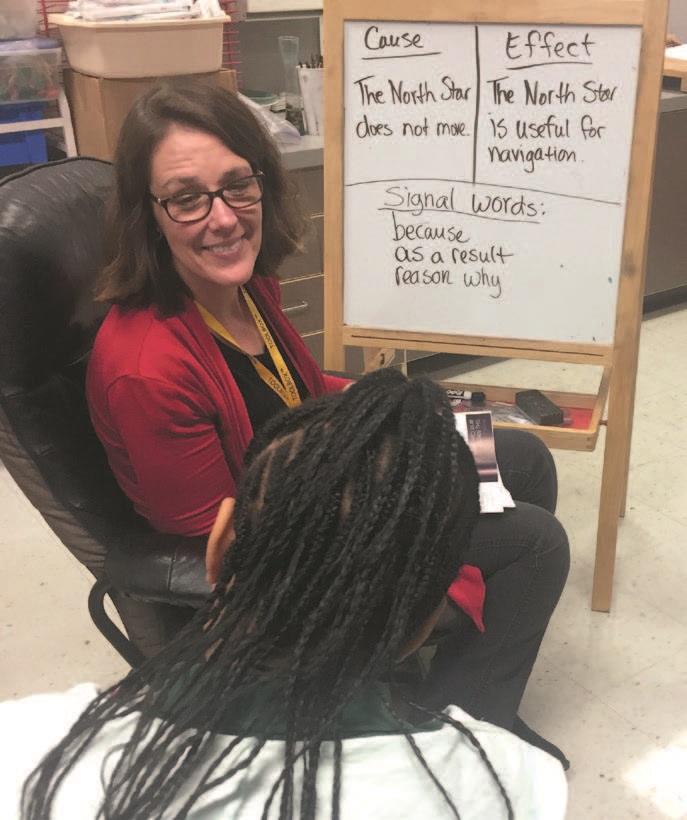

A Comprehension Focus Group provides the forum for a teacher to observe student use of language structures, which leads to a deeper understanding of text reading and language development.

At Zuniga’s school, in years 1 and 2, five teachers were trained to provide intensive reading, writing, and oral language instruction to the lowest-performing students in grade 1. Through this training, teachers developed expertise in literacy acquisition theory and instructional strategies, preparing them to provide colleague support to other teachers in their building. In year 3, five additional teachers embarked on the Comprehensive Literacy and Comprehensive Intervention models to implement a framework for literacy in their classrooms that included Reader’s Workshop and small, differentiated reading, writing, and oral language groups. Each of these teachers worked collaboratively in monthly meetings with their grade-level and intervention colleagues to analyze the literacy progress of the lowest-performing students. The goal was to build toward transfer of learning across contexts—in both classroom and intervention settings—along with increasing congruence of teaching strategies and teacher language. Zuniga also implemented Descubriendo la Lectura (Reading Recovery® in Spanish) as an early literacy intervention that supports both language and literacy development, and also includes systematic professional learning for teachers. Implementation includes a district or consortium that employs a specially trained teacher leader who manages implementation of the model, including training the teachers, overseeing data collection and analysis, and providing ongoing PD for trained teachers. The teacher leader and trained teachers can provide PD and training for classroom teachers who have ELs and other students who are struggling to acquire literacy. They can lead professional learning communities or grade-level teams and guide teachers as they learn strategies for supporting language and literacy development.

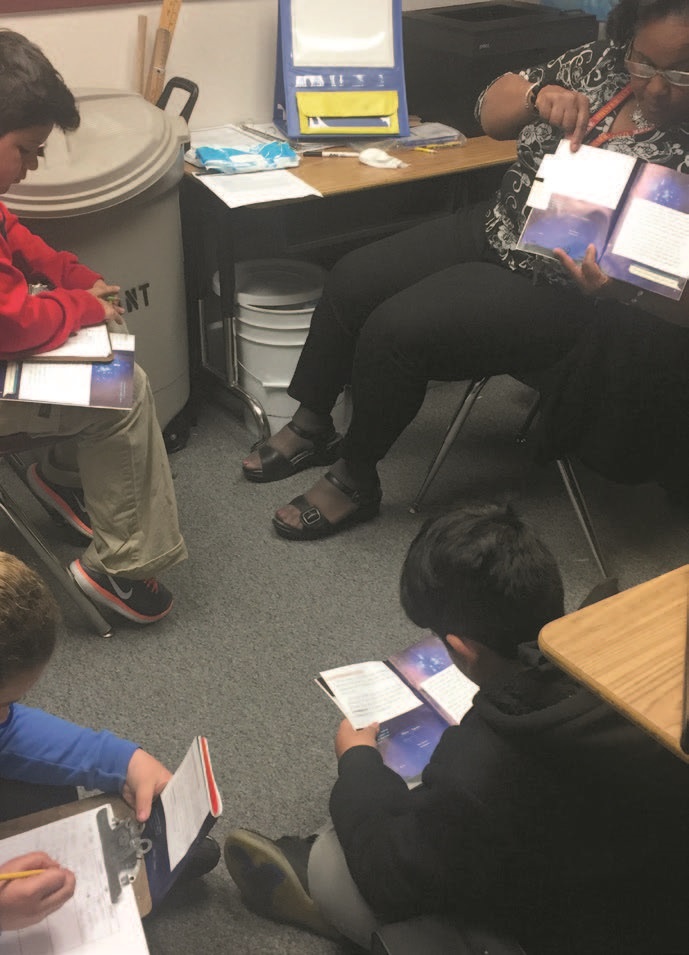

A reading intervention teacher provides a second tier of small-group instruction during the daily Literacy Block, in collaboration with the classroom teacher. The ultimate goal is transfer of learning between the instructional settings.

By the end of year 4, the school’s literacy data showed promising outcomes:

- 70 percent of students reached proficiency on Beaver and Carter’s Developmental Reading Assessment.

- English learner redesignation rate soared from 3 percent to 25 percent.

- For two years in a row, no students were retained.

- Special education identification was reduced from 12 percent to 8 percent.

- State assessment ELA scores rose by 5 percent.

Teaching With Transfer in Mind

Why do support teachers pull out English learners and other students to drill down on sounds, spelling patterns, vocabulary lists, or similar items, and then expect students to transfer that learning to the classroom? A shift from this isolated practice, often provided in a different setting, to an integrated model of tiered interventions more effectively supports students’ transfer to classroom contexts.

One example of integration and collaboration around teaching practices is the California English Language Arts (ELA)/English Language Development (ELD) Framework, which emphasizes the connections between ELA and ELD in its very title. The concept is based on transfer, the idea of amplifying core literacy instruction in small group support services, rather than isolating and possibly working in a silo or uncoordinated way that works against transfer.

This is a logical approach. For example, if we want to get better at playing tennis, we can work on the forehand or serve, but as tennis learners, we understand from the beginning how the forehand and serve are used in the whole game. For literacy and language learning, the same connectedness at the understanding level is needed for the teachers to design the appropriate scaffolding so that transfer is easy rather than being an extra burden on the students.

Samuel, a first-grade newcomer at Zuniga’s school who scored at a beginning level of English (CELDT) in fall 2016, was served in small, differentiated groups with his classroom teacher and a reading teacher for both oral language and reading/writing instruction. After four months of school, he was still reading at a beginning first-grade level and speaking English in simple sentences. He received Reading Recovery lessons for 14 weeks that provided targeted reading, writing, and oral language development opportunities. By the end of May 2017, he was reading above grade level and was speaking English with prepositions and some conjunctive phrases. One of the keys to Samuel’s success was that his teachers worked together on his behalf to be sure his English language development goals were addressed with congruency to his reading and writing instruction. This collegial work allowed for transfer of learning across several contexts (tiers of intervention) for Samuel.

Developing a Global Community

The first step in supporting teachers to more effectively serve ELs is taking time to assess the current status of literacy teaching and learning in your school. Look closely at the range of services and the connectedness of all the programs in the school, and consider:

- Are students’ English language development needs being met within literacy instruction, or is language learning and support separate?

- How are teachers and students connecting language development and literacy learning?

- What structures are in place for teachers to engage in ongoing learning, collaboration, and sharing?

- Are teachers learning to teach students, or learning to teach a program?

- What systems are in place to ensure that students don’t fall through the cracks?

Across the U.S., changing demographics are resulting in large increases in numbers of English learners speaking hundreds of different first languages. Whether schools thoughtfully plan and implement congruent instruction for ELs will determine their success in the years to come. The impact on student growth when language and literacy are developed together in the classroom, with teachers having collaborative partnerships, is beyond test scores. It is about developing the global community of 21st century learners.

Adria Klein is the Reading Recovery Center director and trainer at Saint Mary’s College of California.

Janeen Zuniga is an elementary principal in the Antioch Unified School District and a Reading Recovery teacher leader.

Allison Briceño is an assistant professor at San José State University and a Reading Recovery/Descubriendo la Lectura teacher leader.

Annette Torres Elías is an associate professor and a Reading Recovery/Descubriendo la Lectura trainer at Texas Woman’s University.

Copyright © National Association of Elementary School Principals. No part of the articles in NAESP magazines, newsletters, or website may be reproduced in any medium without the permission of the National Association of Elementary School Principals. For more information, view NAESP's reprint policy.

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| Klein-etal_SO17.pdf | 1.12 MB |